Abstract

This exploratory study investigates how digital champions understand barriers in digital government and the strategies that they apply to overcome them. The interviews with digital champions working in and with a variety of U.S. government identifies four barriers and six types of strategies to become digital. Moreover the findings highlight the interconnected nature of barriers and the non-linear quality of strategies and allow the construction of a theoretical model

Context

For adopting and implementing digital technology people are needed to drive digital government processes, here considered as digital champions. Their engagement is necessary to overcome bureaucratic obstacles towards the implementation of digital government plans and technological innovation within the public sector (Sandoval- Almaz´an et al., 2017). Till now, there has not been a systematic effort to map strategies which digital champions can leverage on to overcome structural and cultural barriers regarding digital government. Structural barriers in our understanding contain technological barriers (infrastructure, lack of interoperability, data access), organizational factors (lack of strategy, human resources, digital skills, capacities of managers), legal and ethical factors (lack of citizen trust), and factors related to limited budgets or competition for financial resources (Barcevicius et al., 2019). These are closely intertwined with cultural barriers like risk aversion and fear of change. In general cultural barriers can be seen as established ways of doing things in bureaucracies (e.g. possesing a bureaucratic culture) and having a lack of organizational leadership without a clear vision and strategy towards transformation. Generally, research on transformation processes recommends that public administrations should adapt a holistic approach incorporating both cultural and structural strategies to ace digital transformation (Mergel, Edelmann, & Haug, 2019). Still, there is no clear indication in the research on digital government about what types of strategies might be effective in overcoming barriers to digital government. Which structural and cultural barriers in digital government exist and which strategies digital champions should employ to overcome them is topic of this article.

Method

As part of the exploratory analysis qualitative expert interviews with digital champions were conducted. The 55 selected interviewees are digital champions working in and with a variety of U.S. government institutions. The analysis of the interviews was carried with a deductive and inductive coding to identify barriers and strategies most salient in advancing digital government, in line with the approach of Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton (2013).

Results

55 interviews allowed the identification of four types of barriers and uncovered six types of strategies prominent in how digital champions describe digital government. In general cultural strategies were more prominent than structural strategies. Below the concrete barriers are highlighted. In the following chapter strategies and practical implications will be presented.

Structural barriers

1. Adequate capacities and resources

Adequate resources and capacities are needed to develop innovative solutions for digital government. Besides the necessity for technical skills, non-technical skills like leadership and management, were mentioned by digital champions. Moreover, several respondents emphasized a mismatch between the institutional roles mandated to Chief Information Officers (CIOs), and the necessary “people skills” needed to manage transformational processes. Lastly, interviewees described challenges associated with hiring people with the appropriate skills, regularly attributed to an inflexibility around processes and rules codified through very formalized processes for hiring.

2. Governance structures

Our Interviewees stated with stunning consistency, that the role of the CIO is not well positioned to facilitate digital transformation. Mostly because the role demands both technical and managerial experience. According to the interviewees, few CIOs live up to this claim. Another crucial barrier is the lack of coordination and the resulting emergence of rigid institutional silos hindering collaboration across institutions or teams.

Cultural barriers

1. Institutional Culture

Results indicate that cultural barriers are more salient when it comes to digital government transformation. Broadly understood as organizational cultures, interviewees describe their working environment often as risk averse with a clear lack of incentives to think out of the box and deviate from the way thins had always been done. Particularly in the context of technology this phenomenon is extremely pronounced and civil servants stick to standard processes. Especially employees with a strong professional ethos and specific expertise struggle to adapt new methods (e.g. agile project management).

2. Lack of awareness

Our analysis moreover indicates that civil servants tend to have a lack of technological familiarity or literacy. In concrete, employees and mangers sometimes don’t know what they don’t know. From personal experience our interviewees emphasized that they observe a lack of awareness about the value that technology could add, rather than awareness of technology per se. Additionally, digital champions noted the exacerbating effect that vendors have on digital government. They drain government resources, perpetuate low capacity in government, and diffuse notions of technological solutionism, while holding monopolies on actual technology solutions.

Strategies and practical implications

Leveraging structural strategies

1. Upskill employees and restructure

Strategies for leveraging the structural aspects of digital government were in contrast to cultural strategies not widely represented in the interview responses. Most often mentioned were upskilling strategies, involving training, capacity development or professional development activities. Apart from that strategies for restructuring government institutions (e.g. creating technology teams that are cross-functional) were often mentioned to break silos and the appearance of dozens of separate tech teams. Some digital champions also called for a reconstruction of the CIO’s roles, through the change hiring processes and mandates.

Leveraging cultural aspect of digital government

1. Align to modern world

In modern world there is literally nothing that is not mediated by technology. Governments have to face this new normal and bring expectations of civil servants, public administrators, and institutions into alignment. Our respondents expressed a hope that private sector thinking could disrupt governmental inertia and path dependency. This could happen on the one hand through hiring from private sector (e.g. using fellowship programs to move projects along), partnering and collaborating with private sector, or through highlighting the values of digital tools using methods like story telling. This might be essential for building momentum for digital government evolution.

2. Build networks

For digital champions it is also important to learn from peers across contexts, which often involved exchanging highly specific knowledge and experiences in networks. This unfolds the potential to replicate digital service projects and organizational processes across contexts leading to a diffusion of good practices with digital technologies in government.

3. Build legitimacy

New technology and innovation in sometimes still perceived with suspicion or aversion in government. Therefore it is indispensable to simply demonstrate the value that digital tools and processes can add to core government activities. Especially decisions makers have to experience these digital tools in order to understand the values which can be gained. Here, playbooks were seen as a prominent strategy to build legitimacy.

4. Leverage on crisis

Crisis align people’s interest. Leverage on these opportunities in order to embed aspects of digital government in institutions. Respondents described strategies such as technology fellowships as creating opportunities for organizational transformation through aligning the work of digital service teams with the top priorities of political leadership.

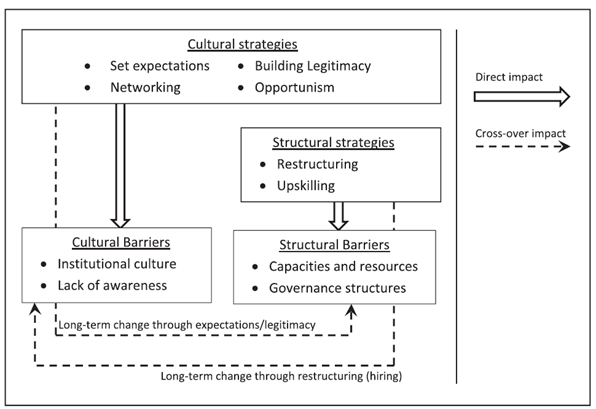

5. First concentrate on cultural structures

Cultural and structural strategies were closely intertwined with barriers and in which cultural change in institutions led slowly and incrementally to structural change.. In our perspective upcoming digital champions should apply cultural strategies first, since they are having cross-over impacts on cultural as structural barriers (see figure 1).

Structural barriers (e.g. top-down structures, bureaucratic processes) were often seen as necessary evils which needed to be managed and navigated, not barriers that could be overcome. Even not codified in law, structural barriers like technical capacities, institutional silos, and formalized hiring processes are viewed as reinforcement of so many other barriers that they seem intractable. Through the usage of cultural strategies digital champions can navigate (and sometimes avoid) structural barriers in order to achieve progress in becoming digital.